Self-publishing Children's Books - A Look at the Numbers

Last year, I ran an anonymous survey for traditionally published children's authors. Hundreds of authors participated and the results for young adult, middle grade, and picture books categories painted a detailed picture of the life and livelihoods of children's authors.

After I published these results, a few people contacted me saying it's easier/better/more profitable to self-publish. I had guesses but not enough information to respond or verify. I wanted to know more, so from January to May (2018) I opened a survey for "Non-traditional Children's Book Publishing."

This anonymous survey was for authors publishing children's book(s):

1) under their own publishing brand (or under the label of a close friend/family member)

or

2) through a company that provides minimal to no editing/marketing assistance (including print on demand)

or

3) through a company where the author pays for or crowdfunds at least part of the publishing project.

Authors identifying as "self-published" or "indie" were welcome to participate as long as they met these requirements. In the end, seventy-eight authors submitted answers. THANK YOU authors!

A note about the term "indie author"

Some people thought I should call this survey an "indie author survey" instead of "non-traditional" or "self-published." However, while advertising for the survey, "indie" created some confusion. Some people seemed to think indie means published under a small, traditional, and advance-paying press. Not so. Indie means the author manages their own publishing brand and becomes their own house. Because of this confusion, I chose to identify all authors participating in the survey under the umbrella term "self-publishing." Feel free to discuss this more in the comments.

The authors taking the survey were:

Gender: 84.6% female, 14.1% male, 1.3% husband/wife team, 0% non-binary

Ethnicity: 8.2% Hispanic or Latino, 1% Filipino-American, 1% Ukrainian, and the remainder simply identified as "not Hispanic or Latino"

Race: 87% White, 3% Black or African American, 3% Mixed, 1% Middle Eastern, 1% Filipino, 1% American Indian or Alaskan Native, and 4% didn't answer

Age: The ages ranged from 19 to 85 years old. The average age was 46.

Country of residence: 85% USA, 4% Canada, 4% UK, 3% Australia, 1% Denmark, 1% Brazil, 1% New Zealand, 1% Singapore

Types of creators: 69% authors, 28% author/illustrator, and 3% illustrator

Writing: 88% fiction, 12% nonfiction

Intended audiences: 52% picture book, 2% chapter book, 33% middle grade, and 13% YA

I didn't have a large enough sample to feel confident breaking the data into sub-groups. However, if there's interest, I can look up specific information, like "30 year old female Hispanic picture book writers from the United States."

Levels of experience:

Authors rated their levels of experience in writing, editing, and marketing on a scale from 1 (hobbyist) to 5 (expert).

Most authors in the survey were confident in their writing and editing abilities. However, only about 20% of self-published authors considered their marketing skills above average. Authors rating their marketing skills at a four or five sold about twice as many books as those rating themselves at three or lower.

That said, the two bestselling authors rated their marketing skills as average. Both these authors paid for marketing and other services prior to releasing their books.

The third bestselling author, rated her skills as excellent (5) in writing, marketing, and editing. This author did not pay for marketing services, only for illustration/design services, prior to publication.

All authors selling in the top 30% invested money in their books prior to launch, except one. Most (70%) published under their own brand label, and most (74%) have multiple self-published books. I created a word cloud of the most common expenses these bestselling authors experienced. Larger words means more of the authors experienced these expenses, not necessarily that one type of expense was larger than another.

Now, let's take a look at authors in the bottom third of the sales numbers. On average, these authors rated themselves slightly lower in writing and marketing compared to the top third. However in editing, they rated themselves slightly higher. Specifically, writing: 3.6 vs 4.0, editing: 3.8 vs 3.7, marketing: 2.3 vs 3.1. I looked through the data and tried to find more of what set them apart from the top third.

A few things stood out among the bottom third.

Most only had one self-published book (67%)

They were the least likely to invest financially in their publishing project (30% spent $0 upfront on their book)

On average, those publishing in the bottom third spent less time on their project

No one in the top third spent less than six months on their project vs. 18% of the bottom third

Still, with every rule there's an exception:

Some people in the bottom third invested in their projects and still had poor sales numbers, and one of the top earners didn't invest any money upfront in his/her project

Some spent years on their project and still only sold a few copies

We'll return to financials later, but for now let's talk about...

Why do authors self-publish?

Authors chose self-publishing for a variety of reasons, most of them personal. In fact, only about 5% of self-published authors indicated "making money" was their primary goal.

Suprisingly, none of the top 10 income earners listed "earning money" as their primary goal. According to the survey results, publishing with the goal of making money doesn't necessarily bring home the bacon.

About half (48.7%) of all surveyed queried traditional publishers before deciding to self-publish. Here's the breakdown of why authors switched from querying traditional publishers:

The most common reason people left traditional publishing is because they were unsuccessful finding a publisher. "Other" reasons people switched from traditional publishing included many varied responses like, "I was getting a lot of interest from fans in pre-marketing" and "Self-publishing just happened for me."

Do traditional publishers sign contracts from self-published works?

Rarely. One author in the survey had his/her self-published book picked up by a traditional publisher. This authors sold 10,000 copies of his/her book prior to being contacted by a traditional publisher. If you're hoping to take this route, be prepared to sell a lot of books on your own first.

Is self-publishing a good way to attract a traditional publisher's attention?

No. Self and traditional publishing are mostly orthogonal career paths. The vast majority (99%) of self-published titles are not picked up by a traditional publisher, and most literary agents won't represent self-published titles.

However, it's possible to pursue self and traditional publishing concurrently. Many self-published authors also have experience with traditional publishers.

8% of the authors had traditionally published at least one book before self-publishing

Most (60%) of the 10 highest income earners were traditionally published before self-publishing

Most (80%) of the 10 highest income earners had writing income outside self-publishing

It's possible to switch back and forth between self and traditional publishing. However, self-publishing is not usually considered a "resume builder" in traditional publishing.

Did most authors accomplish their primary goal with self-publishing?

Yes.

The average rate of satisfaction was favorable: 6.8. No author felt like they completely failed at their primary goal, and a few authors (5%) were totally satisfied with the product. Half of the authors completely satisfied with their project had the goal to "create something memorable for friends and family."

Reaching child readers and establishing themselves as an author were the most common reasons people gave for self-publishing. Beyond these leading reasons, the authors most likely to be disappointed were those hoping to make money. Satisfied authors published for a variety of reasons ranging from creating social change to catering to a niche.

Notably, one author wrote with the goal to "change the world" and was more than half-satisfied with the outcome. Overall, most people self-publishing were happy with their end product.

Now for a less subjective question...

Can you earn a living self-publishing books for children?

Yes.

One person in the survey earned $40,000 self-publishing last year. Here are a few helpful facts about this successfull self-published author.

This person:

was traditionally published multiple times before making the leap to self-publishing

has self-published around 30 books

publishes nonfiction

created his/her own brand and publishing house

paid up-front for professional illustration

treats his/her writing like a business

Two other people in the survey earned over $10,000 last year self-publishing.

Based on this data:

only around 1% of people self-publishing for children earn a living off it.

about 3.7% earn $10,000 or more a year

It is possible to earn a living self-publishing for children, but it's rare.

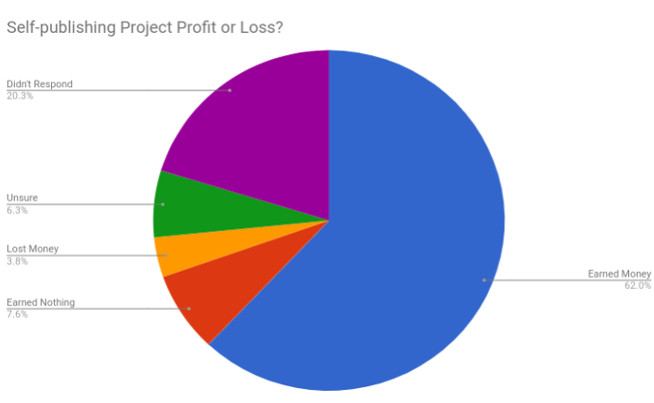

Is self-publishing profitable?

Mostly, yes.

At least 62% earned some money self-publishing.

Many people answered this question with vague answers like, "I made enough to pay for my next book," or "I didn't make much."

Of those that answered with a numeric value, the average (mean) amount earned on their most successful self-publishing project was about $2,900.

Here is a visual of that data spread. (Each blue line in the graph below represents one survey response.)

Since the top earners skew the mean, I also highlighted the middle-most (median) profit amount above. The median amount an author made was $600. However, it should be noted that many authors did not answer this question. If authors didn't give me a number, I didn't include them in the graph above. Many people indicated they lost money with comments like, "Still selling to make the money I spent." So the true median profit is likely lower.

Do authors selling the most copies make the most money?

It's unclear. Authors selling the most copies were the most likely to invest in their projects. Not all of them made enough money to break even.

Very few of the highest sellers disclosed finances. Fortunately, the author selling the highest number of copies did. This author made about $30,000 on his/her most successful project. After expenses, he/she earned $0.87 per book (roughly the same amount earned by a traditionally published author depending on the royalty rate).

Authors selling in the top 30% made less per book than authors selling in the bottom 30%, but their annual incomes were higher on average. However, given that many authors did not answer financial questions, it's possible that up to 30% of self-publishing projects for children lose money.

From the data I do have, self-published authors made on average $2.70 per book sold.

Self-publishing vs. Traditional Publishing: How do copies sold compare?

The following charts compare average copies sold by publishing path selected, using mean and median values as benchmarks.

An author selling a book to a no-advance paying traditional publishing house can expect to sell about as many copies as if they had self-published: 477 books. On average, advance paying houses sell significantly more copies than non-advance paying publishing pathways. As always, there are exceptions. The bestselling self-published author in my survey sold 35,000 copies. Here's the spread of copies sold for self-published children's authors.

Here's the same graph with a call out box that better shows the spread for most authors:

According to the data, self-publishing sales follow a roughly exponential curve. A few do very well. However, 25% of self-published children's books authors sell fewer than 100 books.

Self-publishing vs. Traditional Publishing: How do annual writing incomes compare?

The average incomes of traditionally published authors were higher than those of self-published authors.

75% of traditionally published picture book authors made more than $1,000 last year, 80% for middle grade, and 66% of young adult authors

20% of self-published picture book authors made more than $1,000 last year, 27% for middle grade, and 40% of young adult authors

However, when you look at annual writing incomes for authors publishing at no-advance houses, the averages are very comparable to self-publishing.

Other important considerations for self-published children's authors

Self-published authors should retain the rights to their work.

99% of the authors in the survey retained all their publishing rights no matter what services they used to publish, including 2% who shared rights with an illustrator.

1% gave up rights to a company

Most of the authors (65%) published under their own brand

Most of the authors (95%) had their book available in print

77% of the authors used Print-on-Demand (POD) to publish their book and most seemed happy with this printing option

None of the authors had wide physical distribution in bookstores

While many had their books available for purchase online through bookstores (often as POD), very few are stocked in a brick-and-mortar store

One author commented that physical distribution isn't desirable anyway because selling in bookstores makes the profit margins too tight

Library distribution was a little better for self-published authors

59% of authors had their book in at least one library and 13% had books in many libraries

20% used pay-to-publish or vanity houses

none of these authors were in the top 50% of annual earners

half of these authors felt the publisher failed to deliver what was promised

Parting Thoughts

Self-publishing isn't inherently better or worse than traditional publishing. It's a just different experience, easier in some ways and harder in others. Whether or not you decide to self-publish depends on your goals, needs, and skills as an author. Here are a few key takeaways from the Non-traditional Children's Publishing Survey.

The Good

Self-published children's authors (SPCA) can (and usually do) bring books to market more quickly than traditional publishers

SPCA have more control over the finished product

SPCA can cater to niche markets

With careful planning, hard work, and business savvy, SPCA can earn as much or more than some traditionally published authors

Most SPCA were satisfied with their publishing experience

Most met their primary goal in publishing, and often these goals were very personal

Most made a profit

The Difficult

Self-publishing carries more risk than traditional publishing

up to 30% of SPCA lost money

Most SPCA sell fewer than 1,000 books per project

The SPCAs with the highest incomes were mostly authors with experience publishing books traditionally

Most SPCA struggle with marketing

Distribution to stores and libraries was an obstacle for many SPCA

online sales were the predominate method of moving books for SPCA (which is neither good nor bad, just an observation.)

Do you have experience with self-publishing not reflected in these numbers? I've reopened the survey. Feel free to continue contributing your experiences: Non-traditional Children's Author Survey

I hope this information was helpful. Do you have a question not answered in this post? Comment below. If there's an answer in the survey data, I'll dig it up for you.

Happy writing trails and best wishes on your publishing journey!

Looking for more content like this? Subscribe to my newsletter.

Hannah Holt is a children’s author with an engineering degree. Her books, The Diamond & The Boy (2018, HarperCollins/Balzer+Bray) and A Father’s Love (2019, Penguin/Philomel) weave together her love of language and science. She lives in Oregon with her husband, four children, and a very patient cat named Zephyr.